The Architect’s Newspaper:

Crit> Alternative Domino Proposal. Recounting the bittersweet history of Brooklyn’s Domino Sugar Factory, Molly Heintz says the city deserves better.

To those of us in the neighborhood, long-suffering Domino feels more like a person than a project. Reborn as a development site in 2004, the defunct sugar refinery complex on the Williamsburg waterfront has gone through a rocky childhood. For the last decade, controversy has surrounded its use and financing. Now, Domino is about to enter what’s sure to be an awkward adolescence—now that the City Council signed off on the latest deal proposed by developer Two Trees and supported by the New York City Planning Commission, the 11 acres will become a construction site through at least 2023.

The result would be 3 million square feet of offices, retail, and residential space housed in a series of buildings designed by the architecture firm SHoP. City Hall is already high-fiving, but city leaders should consider that now and in the future the communities in all five boroughs deserve better.

Recent press around Domino has focused on the increase in affordable housing units hammered out between Two Trees and the City. The current deal, spearheaded by planning commissioner Carl Weisbrod and deputy mayor for housing and economic development Alicia Glen, has been hailed as a coup for the de Blasio administration. Two Trees agreed to 700 affordable units, an increase from 660, or 30 percent of the planned 2,200 units. But at what price? More square feet. And that continues to be the rub for members of the community: the project’s sheer scale compared to its context. Two trees claims the project scale—the tallest building is now 55 stories—is contextual if compared to the neighboring Williamsburg Bridge, a flawed point of reference when current zoning requires buildings just off the waterfront to be six stories or less.

Despite SHoP’s new design, other serious scale-related questions still linger. For example, the 2010 Environmental Impact Study lists building shadows as an “unavoidable adverse impact.” A 2013 follow-up report revising the findings in light of the SHoP plan states that the shadows will be better, faint praise considering the widespread gloom that would have been generated by the previous scheme. It is also a claim that should now be revisited given the new building heights and the fact that diagrams representing a wintertime afternoon timeframe—when shadows would be worst—are omitted from the 2013 report. The shadows are still severe and will make a large chunk of Williamsburg feel like a village stuck in a deep alpine valley. Transit, traffic, and pedestrians are on a list of other issues requiring mitigation thanks to the outsized project.

Raising these concerns are not just to-be-expected NIMBY objections. A lower income neighborhood until the last decade, Williamsburg and its residents do not have the PR reach or sense of entitlement to speak up that money buys in New York. The community understands firsthand the value of development and the need for affordable housing, but the issue for many residents is a much bigger one: the feeling that Domino is a major lost opportunity for the city.

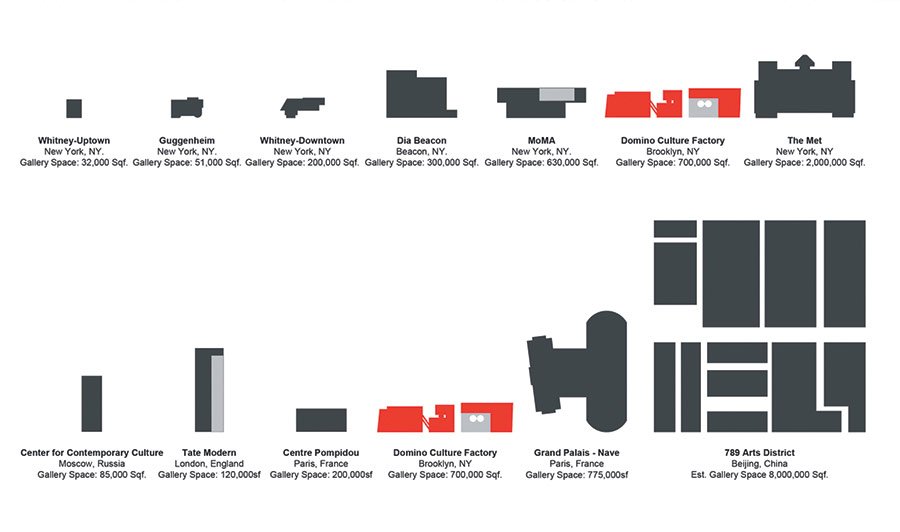

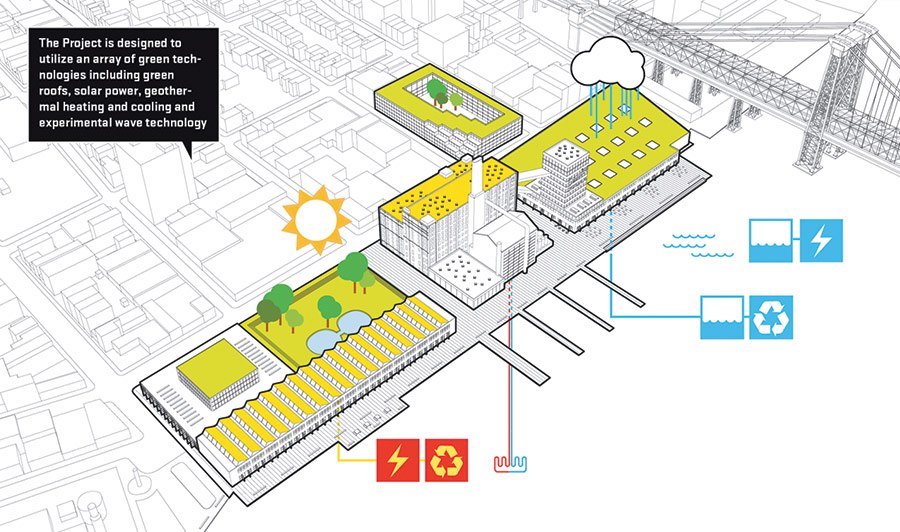

The community group Williamsburg Independent People, exploring alternative ideas, commissioned Jens Holm of HAO/Holm Architecture Office (full disclosure: Jens Holm is the author’s spouse) to help envision a plan that includes the same amount of affordable housing and retail, plus more public space. Recognizing the unique history and situation of the site, this financially self-sustaining scheme takes a page from the adaptive reuse of a London power plant that became a powerhouse cultural attraction, the Tate Modern. It is a plan that doesn’t just benefit the neighborhood or one borough, but would have long-term economic ripple effects for the entire city.

Above all, it underscores the possibility that affordable housing might be able to take forms other than as the stepchild to luxury condos. Disappointingly, architecture critics writing about the SHoP proposal over the past year have stayed focused not on the larger context but the architectural aesthetics, waxing poetic about watching the sun rising in the monumental “O-shaped” building or noting how the new skyline spells “Ooh.” Sure, that is the way it looks if you are sitting in Manhattan. From the Brooklyn side it spells “Hoo.” As in, ha, ha. This is bigger than Two Trees and SHoP.

It is a question of where the city’s loyalties truly lie. Local government should represent not just individuals but be the caretaker of neighborhoods. The balance sheet may now add up in a more equitable way, but looking beyond the numbers, the city still comes up short. Failing to acknowledge the impact on the urban fabric is a problematic precedent for the de Blasio administration, and the City Council should realize that Domino will cast a long shadow.