Davis Brody Bond Architects & Planners with Renfro design Group

Balanced on a pedestal at the end of the Frick Collection’s newest gallery, Diana, goddess of the chase, appears to have just leaped back across Fifth Avenue after a little hunting in Central Park. That this late-18th-century statue by Jean-Antoine Houdon was allowed to emerge from storage and strike a pose against an appropriately sylvan backdrop is one of the highlights of a thoughtful renovation led by Davis Brody Bond (DBB).

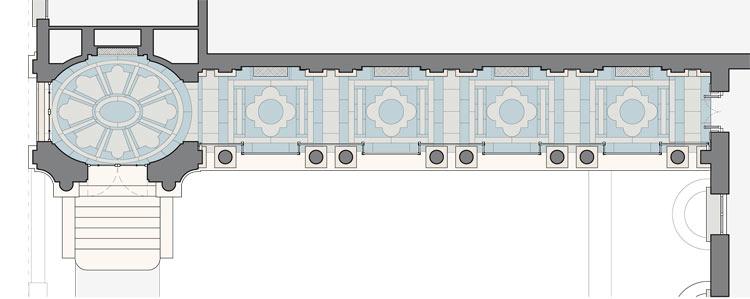

The Portico Gallery for Decorative Arts and Sculpture, the museum’s first new exhibition space in 35 years, was created from a south-facing loggia running along the Frick mansion’s ample front yard. The project came about when a donor’s gift (an extensive collection of porcelain) required additional display space. DBB and former Frick director Anne Poulet decided to take a cue from the 1914 building’s original architect, Thomas Hastings of the firm Carrère and Hastings, who, just after completing Henry Frick’s main house, immediately began sketching up a proposal for a sculpture gallery addition.

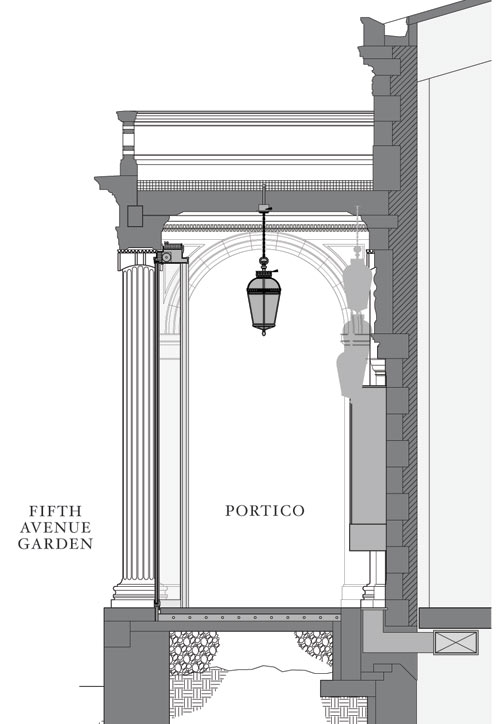

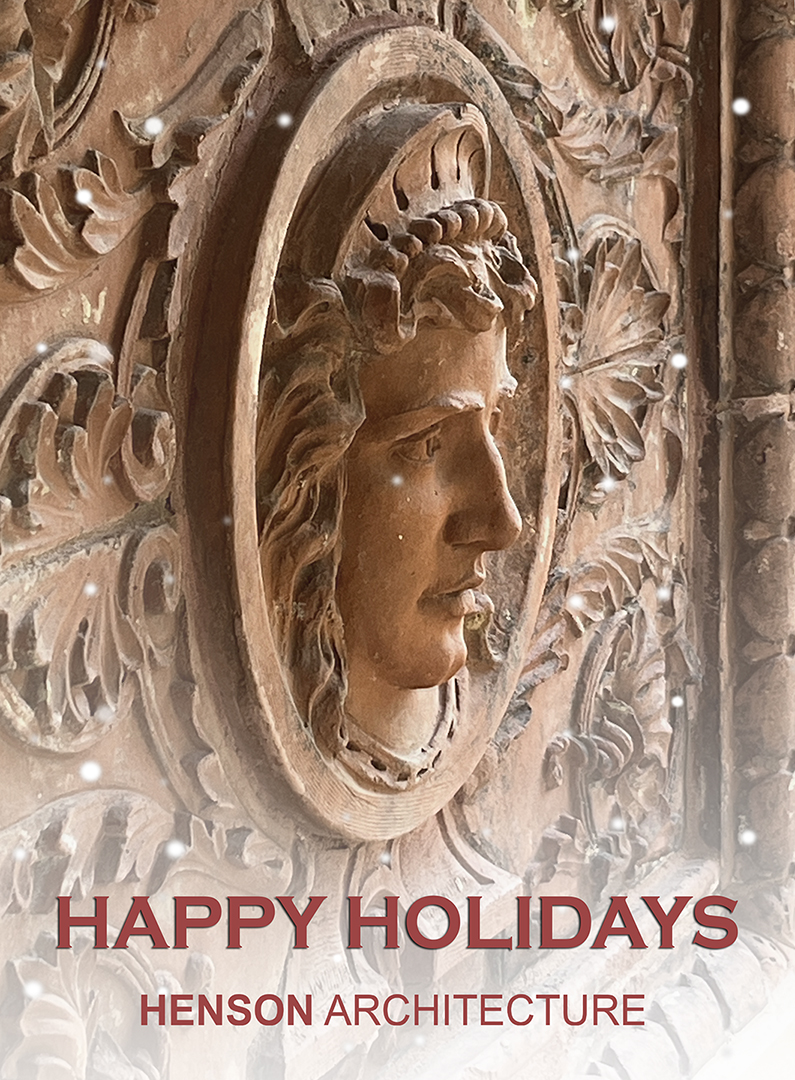

Hastings’ scheme went on hold once the United States entered World War I in 1917 and never came to pass due to Frick’s death in 1919. But almost a century later, that plan to create a sculpture gallery connected to the main house led DBB to consider the disused colonnaded loggia, whose decorative limestone relief carving has been fading due to exposure to corrosive exhaust fumes from Fifth Avenue traffic. Part of the original house, the long and narrow 815-square-foot loggia was accessible from the library, but had long been closed to museum goers.

The new gallery’s southern orientation means copious amounts of sunlight, an issue for paintings but less so for sculpture and ceramics. “We wanted to maintain the character of an outdoor space,” said DBB partner Carl Krebs, whose team specified low-iron glass panels to fill the spaces between the columns. The panels, some of the largest in production at approximately 14 feet by 7 feet by 2 inches, are cantilevered from below, resting in shoes secured 16 inches below the floor. Framed in bronze and set slightly back from the outmost edge of the loggia’s floor, the glass panels defer to the limestone columns, allowing the space to retain its original appearance both from the interior and the exterior.

The loggia’s stone paving was too damaged to be saved, but removing it allowed DBB to install power lines and a radiant heating system below for finely tuned climate control. Ventilation of the space was made easy thanks to a series of existing grates running along the floor of the interior wall, where the gallery’s main display cases are mounted. The grates originally allowed air into servant’s quarters in the basement, and DBB took advantage of the subterranean space to install new air ducts. Lantern-style custom lighting fixtures modeled on those found elsewhere in the house hang from the ceiling of a newly insulated roof; a striking bluestone floor replicates the pattern of the early 20th-century paving, running the length of the gallery and culminating in Diana’s oval rotunda.