Suzanne Labarre reports for Co.DESIGN.

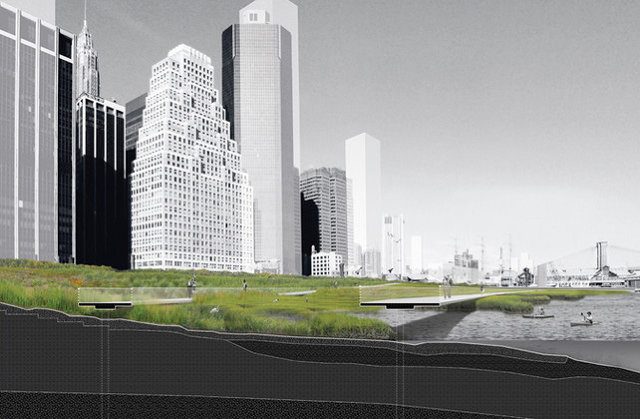

[Image Courtesy of Architecture Research Office]

Diana Balmori, Michael Manfredi, Peter Gluck, and more top architects speak exclusively to Co.Design on how to safeguard cities against the next Hurricane Sandy.

A year after Hurricane Sandy struck the United States, destroying houses and public infrastructure along the Eastern Seaboard, we reached out to several architects and posed two questions: What did you learn from Sandy? And how can architects prepare for the next storm? Their responses, edited and condensed, are below.–Eds

Peter Gluck, principal of the design-build firm GLUCK+

Unfortunately, architects tend to think they can profit from the damage. You wonder if they’re coming in to look at the problems or to get more work. I was appalled to hear that in the first week after Sandy, there were AIA ads for architects needed. It made my stomach turn–architects being ambulance chasers.

One of the obvious things architects can do is design their buildings that are within the flood zones to withstand the flood. We’re doing a project for Duke University, which is in flood areas, on the coast. We placed the second floor, where the expensive lab equipment is located, 25 feet above sea level and the whole building is designed to withstand winds of 140 mph. Buildings on the coast need a lot of structural resistance to the wind itself. And of course, water is a big issue. We placed the science building at Duke very high above sea level and are allowing the first-floor spaces to get destroyed–the first floor is programmed such that it wouldn’t be a disaster if it got wiped out.–As told to Carey Dunne

Michael A. Manfredi, founding design partner at Weiss/Manfredi Architecture/ Landscape/ Urbanism

From our studio research and our own work, we’ve discovered that one of the great lessons is to not rely on a single methodology for accommodating events like flooding. Our very first project at Olympia Fields was designed to accommodate torrential rains and collect water in a safe yet aesthetic manner. In other words, water collection is woven into the core of the design.

In the 25 years since, our practice advocates a multidisciplinary approach to shaping sites and engaging infrastructures. At our newly completed park at Hunter’s Point South, 88% of the shoreline is now soft, which means that it is designed to absorb a severe influx of water. The roof of the park pavilion is designed and constructed to resist hurricane-force winds. This park now represents a first line of defense for the surrounding community, which sat four feet underwater a year ago during Hurricane Sandy.

Infrastructure is often incorrectly perceived as hard and inflexible. These same considerations apply for landlocked sites as well. At the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, our rain gardens and 10,000-square-foot green roof are able to absorb a substantial amount of water without damaging the new structure or this historic site. In this way, we can rely on soft infrastructure that acts as a giant sponge to collect and gradually release large quantities of water over time, instead of all at once. It is our belief that it is now time to design alternate strategies that support resilient and pliable sites capable of absorbing cycles of extreme, unpredictable events.–As told to Suzanne LaBarre

Craig Dykers, principal of the architecture firm Snøhetta

It is important to look at small-scale solutions and legislative guidelines to help prevent loss of life and property. The grand and sometimes epic conceptual thinking is useful, but it should be balanced with immediacy. Simple flood protection can easily be implemented in building construction to ensure their contents are protected better. Beyond this, we must focus on landscape design that augments the natural needs of shorelines and basins where flooding may occur. Educating people who live in flood-prone zones should be more extensive than simply posting evacuation plans. In some places, there are credits given to those who design and inhabit shoreline conditions responsibly, measured by their inclusion of environmentally sensitive planning. –As told to Belinda Lanks

Diana Balmori, principal of the landscape architecture studio Balmori Associates

We need to change to sustainable systems NOW, not in the future. That means nature-based systems that can be implemented very quickly, unlike big hard engineering infrastructure projects, and for less money. Green roofs, green streets, rain gardens, pervious paving, linear parks, floating landscapes (which we are currently working on) are all tools that are immediately implementable and do not cost billions.

Architects need to learn about those soft systems, and landscape architects who do know about them need to develop a richer language and more varieties of nature-based systems. Architects pay little attention to sources of energy, and to where they are placed. Both are issues that have moved to the head of the list and cannot be treated as something the mechanical engineers alone will place in the buildings architects design.–As told to Sammy Medina

John Cary, executive director of the forthcoming Autodesk Impact Design Foundation and founding editor of PublicInterestDesign.org

There’s a lot to be done in terms of minding flood zones and taking those things much more seriously. In the past, we looked at hundred-year worst-case scenarios, and I think we’re going to see a greater recurrence of this kind of thing as the climate changes.

One thing that I don’t believe is going to help a great deal is the proliferation of design competitions and contests that seem to pop up after these kinds of disasters and which frankly don’t address or engage with the real needs on the ground or the kind of readiness that we need to have. We need much more practical solutions that are both preemptive and responsive when something does goes wrong.–As told to Sammy Medina

Stephen Cassell, principal of the architecture firm Architecture Research Office

We had done a research study looking at lower Manhattan, mapping where the flood zones were, and after Sandy, all the research we did proved true–we had predicted which areas would flood. We were happy it wasn’t the worst-case scenario. It’s one thing to know intellectually what will happen–to think, OK, these are the effects of climate change–and a completely different thing to actually see the impact of a devastating storm like this. What we really learned is, we better get cracking in starting to deal with these issues.

One of the most basic things architects can do is look at the levels of buildings and start building more resilient structures, asking questions about various scenarios. What’s going to happen when it floods? What about when the power goes out? Can you open the windows? Is there a place to plug in? And we need to look at the specific effects of Sandy on every type of residential building, so that our rebuilding efforts are not just based on theory but on actual data.–As told to Carey Dunne

Lisa Switkin, associate partner of the landscape architecture firm James Corner Field Operations

James Corner Field Operations is involved in a number of NYC waterfront projects that were deeply affected by Hurricane Sandy, including Domino Sugar and Greenpoint Landing in Brooklyn, Hallett’s Point in Queens, South Street Seaport and Muscota Marsh in Manhattan, and Cornell University NYC Tech Campus on Roosevelt Island. A unique design concept has been developed for each site responding to storm surge, flooding, and the escalating effects of climate change with the deployment of innovative strategies and techniques such as terracing, retention and absorption, wetland creation, elevated bulkheads and walkways and use of riparian plantings and porous materials.

As landscape architects, we are trained to think about larger systems and networks that go beyond project boundaries. This is especially important when considering how to make a project resilient. In addition to raising key infrastructure and utilities and developing hard systems (floodwalls, revetments, levees, and bulkheads), there are a number of soft systems (wetlands, beaches, dunes, and parklands) that can be integrated into projects to help absorb storm and flood events while also enriching biodiversity and open-space amenities. Edges between land and water are where these resilient systems need to be developed, avoiding singular “walls” where possible and seeking instead to thicken thresholds, margins, and intertidal zones.–As told to Suzanne LaBarre