THE ARCHITECT’S NEWSPAPER

Scott Henson Architect with Gilsanz Murray Steficek

Local Law 11/98 is a New York City statute mandating that any building of more than six stories must have its facade inspected once every five years. Scott Henson of Scott Henson Architect was undertaking just such an inspection on the historic 1892 Cleverdon & Putzel–designed Banner Building in Manhattan’s NoHo neighborhood when he discovered something rather disturbing. The structure’s cast iron face—both its decorative elements, many of which had fallen off over the years, as well as its structural supports and bracing—was severely corroded. The condition was even worse on the top two floors, an 1898 addition that featured sheet metal decorative elements, which had deteriorated to the point that, in places, a person could press their fingers through them. Making matters even shabbier, the sandstone pilasters that framed the facade’s cast iron bands had worn down to a faded memory and the original single-paned wood windows had decayed beyond repair.

The building owner and the project team, which included structural engineering firm Gilsanz Murray Steficek and historical research firm Office for Metropolitan History, agreed that the only way to proceed was to restore the facade by making every effort to adhere to its original materials and traditional means of construction.

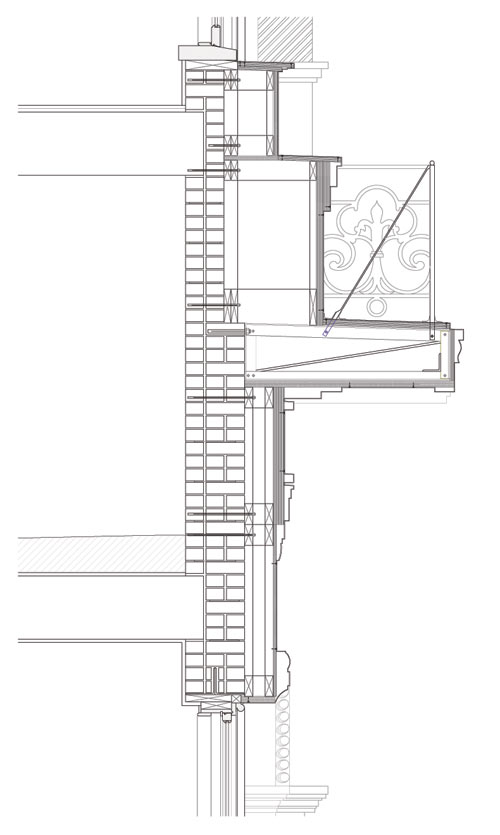

One of the chief causes of the facade’s decline, aside from time itself, was severe water leakage, which had caused the original structural imbeds connecting the cast iron and sheet metal elements to the masonry backing wall to rust to a critical state. The team removed all of the metal elements and inspected them carefully. This analysis revealed that about 80 percent of the cast iron could be reconditioned and replaced on the building. This involved stripping the elements of the ten or so layers of paint that had been applied over the years and patching the odd non-fatal crack with Belzona Supermetal epoxy. Those elements that were beyond repair, or missing, were recast by Robinson Iron in Alabama using samples of the original facade to create new molds. The sheet metal was in worse shape. Approximately half the elements, including egg and dart frieze, scroll moldings, rosettes, and medallion reliefs, needed to be re-fabricated, a job tackled by CCR Sheet Metal in Brooklyn.

|

Once all of the elements had been reproduced or repaired, they were painted patina green (the owner’s preference) and returned to the site, ready for installation. The team designed new structural supports for this purpose: structural stainless-steel bolts that pass all the way through the masonry backing wall and connect to plates on either side, holding the wall in compression. The sheet metal was attached and soldered together, and the cast-iron structure was attached and caulked, making the whole assembly watertight and ready for another 100-plus years of life. The team also hired an artisan who was able to discern the original decorative character of the sandstone pilasters and re-create them with a sandstone patching material from Cathedral Stone.

Replacing the 54 windows required a similarly close historical analysis of the existing conditions. The windows included pulley double-hung varieties and single pivoting sashes with transoms. J. Padin in New Jersey re-fabricated them based on the original historical profiles and materials. Here, however, 21st-century technology was also employed to improve the building’s insulation with high-performance glazing.

As a final touch, the team also replaced the 1970s storefront. With little documentation available, Henson based a new design on what remained at street level as well as on clues implied by the fenestration above. The result is something of a rarity in Manhattan: a vintage cast-iron structure that retains its historic character from top to toe.

Sources

| Sheet Metal CCR Sheet Metal |

Cast Iron Robinson Iron |

Historic Wood Windows J. Padin 973-642-0550 |

Sandstone Cathedral Stone |