Kriston Capps reports for The Washinton Post

The Washington Monument is broken — and it hasn’t looked so good in years. Put in place after the structure was damaged by an earthquake in 2011, the scaffolding creeping up the 555-foot stone obelisk like kudzu has overtaken the memorial. Let’s keep it that way.

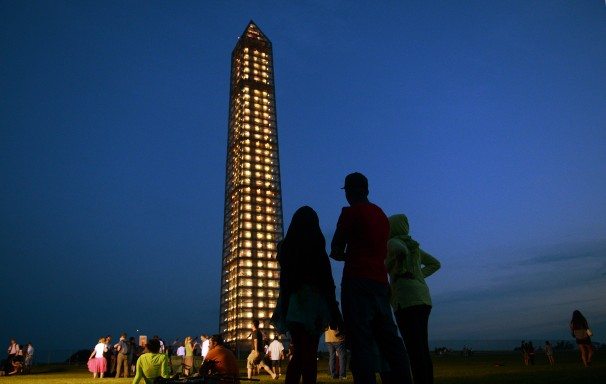

On Monday evening, the National Park Service held a special ceremony to illuminate the monument using more than 400 lights. Lit up like a spectral tower, it has a new civic purpose. “It is a way of saying, ‘We are here, and we will always be here,’ ” National Park Service Director Jon Jarvis said at the ceremony.

The scaffolding does more than that. It gives us an opportunity to reconsider our least enlightening memorial. Although we fawn over other patriotic marble, we don’t get mushy about this monument. In the summer action flick “White House Down,” for example, Jamie Foxx, playing the president, asks the pilot of Marine One to execute an illegal maneuver just so he can get a glimpse of the Lincoln Memorial’s seated statue — the memorial where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963 and President Richard Nixon debated student war protesters in 1970. Meanwhile, on film, the Washington Monument has been destroyed by an earthquake in “2012” and by aliens at least three times — in “Earth vs. the Flying Saucers” in 1956, in “Mars Attacks” in 1996 and in the only season of the NBC sci-fi series “The Event.”

But under scaffolding, the monument is — quite inadvertently — newly relevant. Because Americans broadly agree that governance in this nation is broken, there is a casual elegance to the symbolism of a monument to national unity under construction. We are a work in progress, the cracked memorial reminds. Our union is not perfected.

The same can be said for the Mall. Its defining feature is its indefinability. It represents the vision of no single planner, politician or architect. Rather, as Thomas Luebke, secretary of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, writes in “Civic Art,” the monuments “are the conscious creations first of political will, translated through the work of design visionaries who sought to communicate the political ideals of the nation.” The Washington Monument, at the center of an ever-changing landscape, is always in progress. It belongs under wraps.

Today, the obelisk looks like Germany’s Reichstag in 1995 when, after three decades of debate, the German Parliament allowed artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude to wrap the building in fabric for two weeks. Just five years after the nation’s reunification, this was an artistic accomplishment, but a civic one, too. The Washington Monument looks like it has been encased in an animated version of itself, lines drawn in blue fabric to evoke its brick pattern if that pattern were drawn by, say, the pop artist Roy Lichtenstein.

The monument wore this same armor once before: The National Park Service and Target commissioned architect Michael Graves to design the scaffolding and fabric for a restoration between 1998 and 2000. He managed to encapsulate the world’s tallest stone obelisk in scaffolding that does not actually touch it. It looked cool then, and it looks cool now.

It makes aesthetic sense — and fiscal sense, too. Recession and austerity have led architects to reconsider, reuse and rethink buildings. Consider the “Bubble”: a proposal to build a temporary inflatable pavilion on the plaza of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden right up through the doughnut-shaped building. An unprecedented piece of inflatable architecture, the plan nevertheless ran out of air. Still, for all its novelty, the Bubble was typical of a new instinct to reinvent even things that seem immutable.

It’s too bad that project failed. Washingtonians and tourists might have greeted the seasonal inflating of the Bubble the same way they have received the Washington Monument under scaffolding: with utter delight. At Monday’s ceremony, as officials turned on floodlights level by level, starting from the base, iPhone-wielding videographers turned out in force. Flickr and Instagram are chock-a-block with pictures of the enmeshed memorial. That’s nothing new for the monument, maybe — but it is rare for anything obscured by scaffolding to get so much love.

Washington yields too few opportunities for this kind of “Mission: Impossible” design. We should envy New York for its High Line, a new kind of park built on a former elevated rail by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the same architects who proposed the Bubble. Our neglected civic infrastructure feels no less abandoned than that elevated line once did. For every controversy like the one over a proposed Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial designed by Frank Gehry that some criticize as underwhelming, there are a dozen monuments that go unnoticed. Doughfaced President James Buchanan has a memorial, but how many people know it’s in Malcolm X Park? We don’t want to pave over our history, but we’re allowed to reimagine it.

Surely some will balk at the notion of mucking with the Washington Monument. But history shows that the meaning of even this singular structure has been negotiated over time. Construction, begun in 1848, was completed in 1884, interrupted by a civil war that broke the notion of national unity. The monument’s stones feature inscriptions from the bible, but when Pope Pius IX contributed a block of marble to its construction in the 1850s, members of the anti-Catholic Know-Nothing Party reportedly threw the stone into the Potomac River.

And when the monument was completed, it was hardly thought of as an anchor to an immutableMall. In 1897, philanthropist Charles Carroll Glover, of Glover Park fame, succeeded in having the entire Mall designated a park. President Grover Cleveland had suggested that the strip be dedicated to residents’ vegetable gardens.

The Mall is nearly full. Even looking past our political impasse, the space to build isn’t there. Fortunately, an emerging crop of American designers is used to working under difficult circumstances. Adaptive, sustainable design belongs on the Mall because the Mall serves as a record of the times — from the faux Norman-style revivalist Smithsonian Castle to the poured-concrete brutalist-designed Hirshhorn. And as a nation built on a living Constitution, we should not hold a memorial, even one that honors George Washington, too sacred for future generations to monkey with.

The illuminated monument will continue to dazzle spectators after sundown for six months or so. But even after its cracks are repaired, we should leave it as is: enmeshed by brackets and cross-braces, wrapped up like a sword in its sheath. Let’s make it last. What if we agree to take down the scaffolding when Congress can pass a bipartisan bill declaring it finished? Then we’d know that some national healing had taken place.